As a child, I remember attending birthday parties where we played the game “Pin the Tail on the Donkey”. In this game, a large picture of a donkey is placed on the wall while a blindfolded child, holding a cut-out paper tail navigates their way toward the donkey, attempting to stick the tail in the right place. Meanwhile a cacophony of young voices squeal and yell directives to the blindfolded child to help them find the donkey’s butt.

After 26 years of teaching junior high, I found that the search for a donkey’s butt bears much in common with what all but the brightest stumble towards in their classrooms. An overwhelming number of students enter the 7th grade with just a hazy idea of what actions they’re supposed to follow in order to succeed academically. Thus, many of them conclude they are best served by blindly following cues given by both the teacher and those classmates who look like they know what they’re doing. By midway through the first term, too many learners conclude that the path to academic success runs only through memorization. After all, what else is there?

Nevertheless, there exists another path that proceeds according to a series of steps and insights which render the material not only more easily learnable but more relevant too. I don’t know about you but as a student years ago, in too many classes the singular question that ran through my head was: “why do we have to learn this!” The approach I will present resolves both of these concerns: learnability and relevance.

Traditionally, classroom energy is directed exclusively towards learning various subjects such as English, math, science, social studies though very little is invested teaching students how to learn subjects in general; to process information. Indeed, conversations I’ve had with fellow teachers along the way suggest that few of them have a firm grasp either.

Over the first few years on the job, a major task for teachers is to develop for themselves a sequence of topics in their subject area which becomes their curriculum. As long as their plan results in student marks that follow a standard Bell Curve, very little revision is ever necessary. If a student is having difficulty learning, most teachers are available to assist that student to sort out that isolated difficulty, but never have I seen an entire course designed to address the challenge of teaching students how to learn as a worthy topic unto itself. Yet, I did. I taught annual summer school sessions to incoming 7th graders over the past 15 years devoted to Meta-learning— the formal name for learning how to learn. Nevertheless, I recognized long ago that this mini-course was insufficient to provide lasting meta-learning instruction. Still, something was better than nothing. Therefore, in the spirit of that objective I will formally flesh out the contours of Meta-learning in these words today

So let’s start at the beginning. If you were teaching such a course, where would you begin in your pursuit of a path that would help students achieve awareness of what they are in school to accomplish? I’m a fan of the Socratic method where learning progresses in response to a sequence of questions designed to stimulate deepening levels of thought.

Pause and reflect.

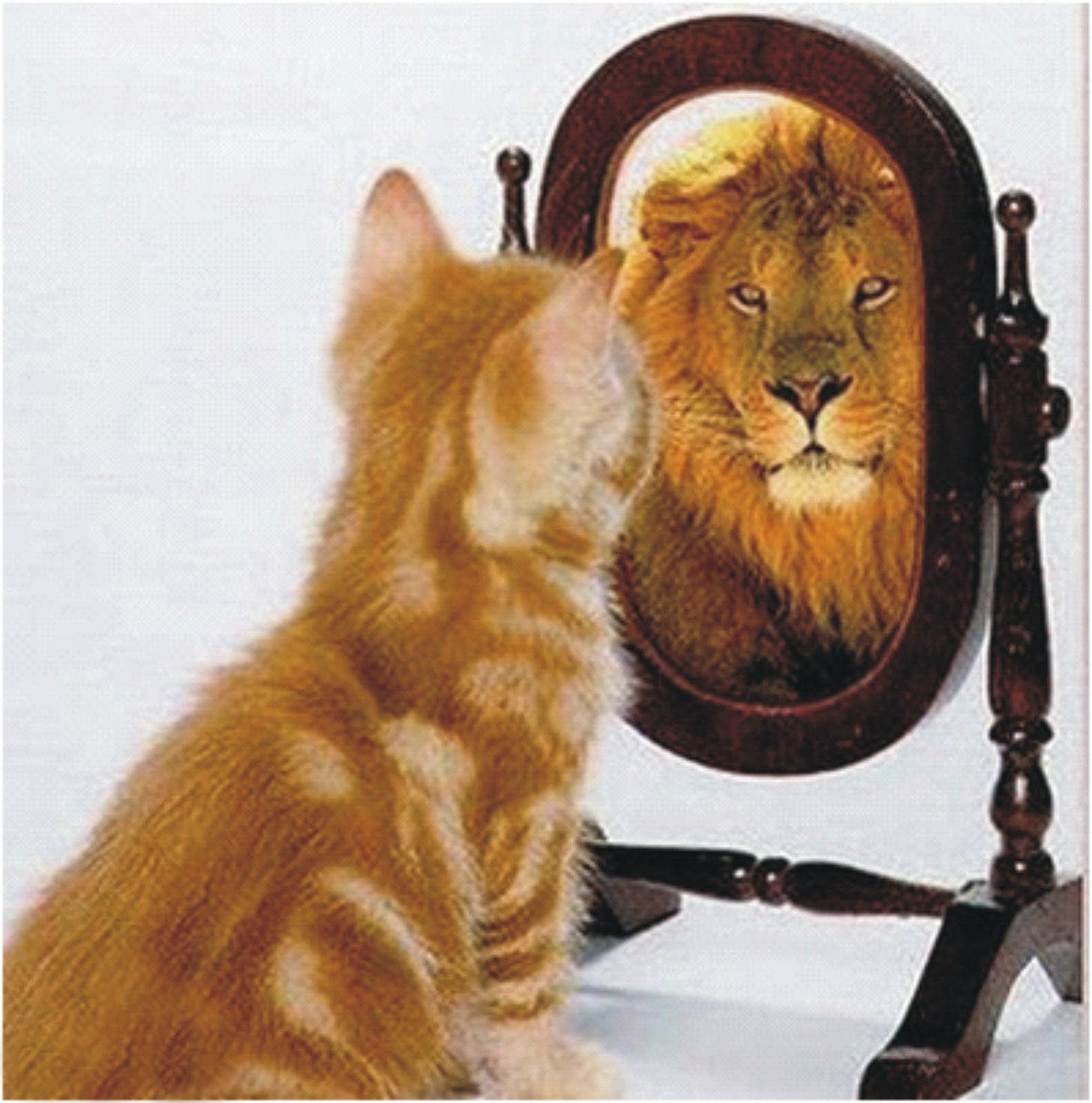

My first question was always “are information and knowledge the same or are they different”? The number of students who simply don’t know or believe information and knowledge to be interchangeable terms is higher than one might think. The truth is they are different— very different. Indeed, their difference illuminates the purpose for attending school in the first place. Students attend in order to learn how to spin information into knowledge, or as the ancient alchemists said it —lead into gold.

So here’s the central distinction. Information is free. We get it from teachers, internet, TV, books, parents, friends, virtually everywhere we look. Nonetheless, the assembly of information into knowledge requires that the information be pushed, pulled and prodded, analyzed and contextualized . In short we have to engage the information following a set of steps to render it knowledge. Until that happens, the information exists as knowledge only in the head of the teacher. Once the steps are followed however, ownership passes to the learner as earned knowledge.

One can use information for instance in a recipe to bake a cake. At first, those printed, baking steps must be carefully followed one by one, constantly checking for equivalence with the cookbook. The cake that results might need to be tweaked for a better outcome next time, though over time and trial and error, the information for how to bake a cake becomes knowledge. Thus the printed recipe is no longer needed and the process becomes property of the cake-maker.

Unlike information presented in traditional classes however, which follows from its subject- matter, the path of information into knowledge always follows the same steps. In other words, the meta-learning path to knowledge for a math or a baking course is the same as for a language or a science course even though the information is entirely different.

There is one basic contrast though between the currency sought in traditional courses and that sought in meta learning. Subject courses are set up to provide information about the learning topic, while meta-learning provides techniques for how to fortify and gain ownership of information. If the content of a meta-learning course is treated as merely information, the course cannot be more than useless. I have to crack a smile when I consider asking students to take a quiz or exam on meta-learning. One can learn techniques only by doing them. Subject courses require a rake while meta-learning requires a spade. The rake covers more territory but the spade allows one depth. Techniques are the means by which students are enabled to process information. Each time a technique is used, its contours become clearer, its efficacy rises as it becomes property in the hands of the young learner.

Before we dive into the four steps of learning, however, there are personal shadow factors residing in each learner which play dominant roles influencing the way they relate to new information. These are insights, without which learning for most students remains a maze. Nevertheless, these factors are largely ignored in favor of the singular outward-focused goal of acquiring information.

After all, there’s always a test to prepare for or a project to complete. Teachers are generally under-the-gun for sufficient time to finish their classwork. I was never able to elevate my Meta-learning class to full-course curriculum status at my school for precisely this reason. Too often sadly, quantity beats Quality. Anything beyond the basics just gets in the way. Little attention is paid to whether students are ready to learn and what impedes them if they’re not. In a meta-learning class, these factors are the basis of the work.

Thank you Karen. Coming from you this means a lot. I left you a little something at KH

Beautifully written by someone who really does know and care. Thank you for this insightful piece and as for politics…yes, thankless but also thinkless at times. Subjects like this one is where the real meat exists and allows our true colors to shine through. Your colors are a hue of fabulously rich stories for all of us to read and then contemplate.